For the first time in a very long time, the Southern Baptist Convention, meeting in Anaheim, Calif., in its 177th year, came very close to having a much-needed conversation on the nature of cooperation moving forward. For some, frustration abounded under the perception that the convention was having trouble determining “what a pastor is.” The presenting issue was over whether or not a Baptist church utilizing the title “Pastor” for a female staff member, other than the senior/lead pastor or an elder (ex: Children’s Pastor, Worship Pastor, etc.), could continue to be part of the Convention. While this is clearly a matter that needs to be agreed upon biblically, and quickly I submit, the larger issue, as some noted from the floor, is much deeper.

First, let’s understand the nature of our national convention of churches. The SBC is an annual convening of likeminded local baptistic churches in the United States, generally agreeing around certain fundamental doctrinal positions, for the purpose of Great Commission advance throughout their neighborhoods and the nations. It is the purpose of this annual convening and its ongoing supporting structure “to provide a general organization for Baptists in the United States and its territories for the promotion of Christian missions at home and abroad,” (SBC Constitution Article II).

Each church is autonomous and voluntarily chooses to affiliate and cooperate with the work of the convention. But independence does not require, nor does it suppose, isolation. Even today we confess, in our BFM2000 Article XIV, that “Christ’s people should, as occasion requires, organize such associations and conventions as may best secure cooperation for the great objects of the Kingdom of God.” Southern Baptists confess a New Testament doctrine of inter-congregational cooperation. Indeed, we are, as is commonly said, “better together.”

From 1845-1925, there was no commonly held confession of faith in the SBC. Most churches affirmed the 1833 New Hampshire Confession and/or the 1689 London Baptist Confession. Some also held to other confessions of faith and practice. In 1925, the SBC voted to affirm its own statement of faith, The Baptist Faith and Message, which intended to capture the voice of the churches on issues they commonly held to be primary for the nature of their missional convening and cooperation. The Preamble of each iteration (1925, 1963, 2000) has included the following qualifying list to facilitate proper understanding of the national convention’s purpose in commonly confessing these doctrines, and the limitations thereof:

- That they constitute a consensus of opinion of some Baptist body, large or small, for the general instruction and guidance of our own people and others concerning those articles of the Christian faith which are most surely conditions of salvation revealed in the New Testament, viz., repentance towards God and faith in Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord.

- That we do not regard them as complete statements of our faith, having any quality of finality or infallibility. As in the past so in the future Baptist should hold themselves free to revise their statements of faith as may seem to them wise and expedient at any time.

- That any group of Baptists, large or small, have the inherent right to draw up for themselves and publish to the world a confession of their faith whenever they may think it advisable to do so.

- That the sole authority for faith and practice among Baptists is the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. Confessions are only guides in interpretation, having no authority over the conscience.

- That they are statements of religious convictions, drawn from the Scriptures, and are not to be used to hamper freedom of thought or investigation in other realms of life.

In its historical governance, the SBC’s Credentials Committee existed only to verify whether a church could seat messengers at the annual meeting. In 2019 SBC messengers voted to change the Constitution to allow for a standing Credentials Committee, with the broader scope of responsibility to determine throughout the year whether a church is in friendly cooperation with the convention based on the Constitution’s Article III which states, among a few other points of consideration, that the church must have “a faith and practice which closely identifies with the Convention’s adopted statement of faith.” (See Bylaw 8.C.3.a. and Constitution Article III.)

The SBC Credentials Committee, as it now stands, is to determine whether a church has “a faith and practice which closely identifies with” the BFM2000. The intention is to maintain general doctrinal consensus within the convention of churches, through the powers of our Constitution Article III, without overstepping the limitations of our Constitution Article IV (“While independent and sovereign in its own sphere, the Convention does not claim and will never attempt to exercise any authority over any other Baptist body”). Because no church is required by our governance to affirm the BFM2000 to become or remain affiliated, it is up to each Credentials Committee, rotating through the years, to determine the level of cooperation and confessional adherence that would constitute “a faith and practice which closely identifies with the Conventions’ adopted statement of faith.” This is why it may seem ridiculous to some in the convention hall that a Credentials Committee would not take action on a church that seems to be clearly in violation of one article, or one portion of one article, of the faith statement. To many messengers it will be a clear-cut issue, while for others it will feel more ambiguous. Where to draw the line is completely left to the discretion of the Credentials Committee, since their constitutional duty is not to determine whether a church has violated one article or another, but whether that church, in its deviation, still has a faith and practice that is close enough to the faith statement to be considered in general alignment with the Convention’s doctrine and work.

Like it or not, that’s where we are. By creating a standing Credentials Committee in 2019 through bylaw amendment, the messengers charged the Credentials Committee with the task of preserving doctrinal unity within the convention of churches. But they did not change the Constitution to give the Credentials Committee the teeth they need to do their work with objectivity.

The conversation we need to be having is on the nature of our missional cooperation moving forward. Should we become, in our national SBC, more like a confessional fellowship of churches requiring all member churches to affirm and operate within the parameters of the faith statement? Or should we continue our historic practice of convening churches with “like faith and practice,” using the faith statement as a general guideline?

I will not attempt to answer that question now. However, I would like to offer the following framework to help lay some explicative groundwork for this much-needed conversation. The first question we should ask, which I attempt to answer in this article as briefly as possible, is: What is the nature of Southern Baptist Cooperation?

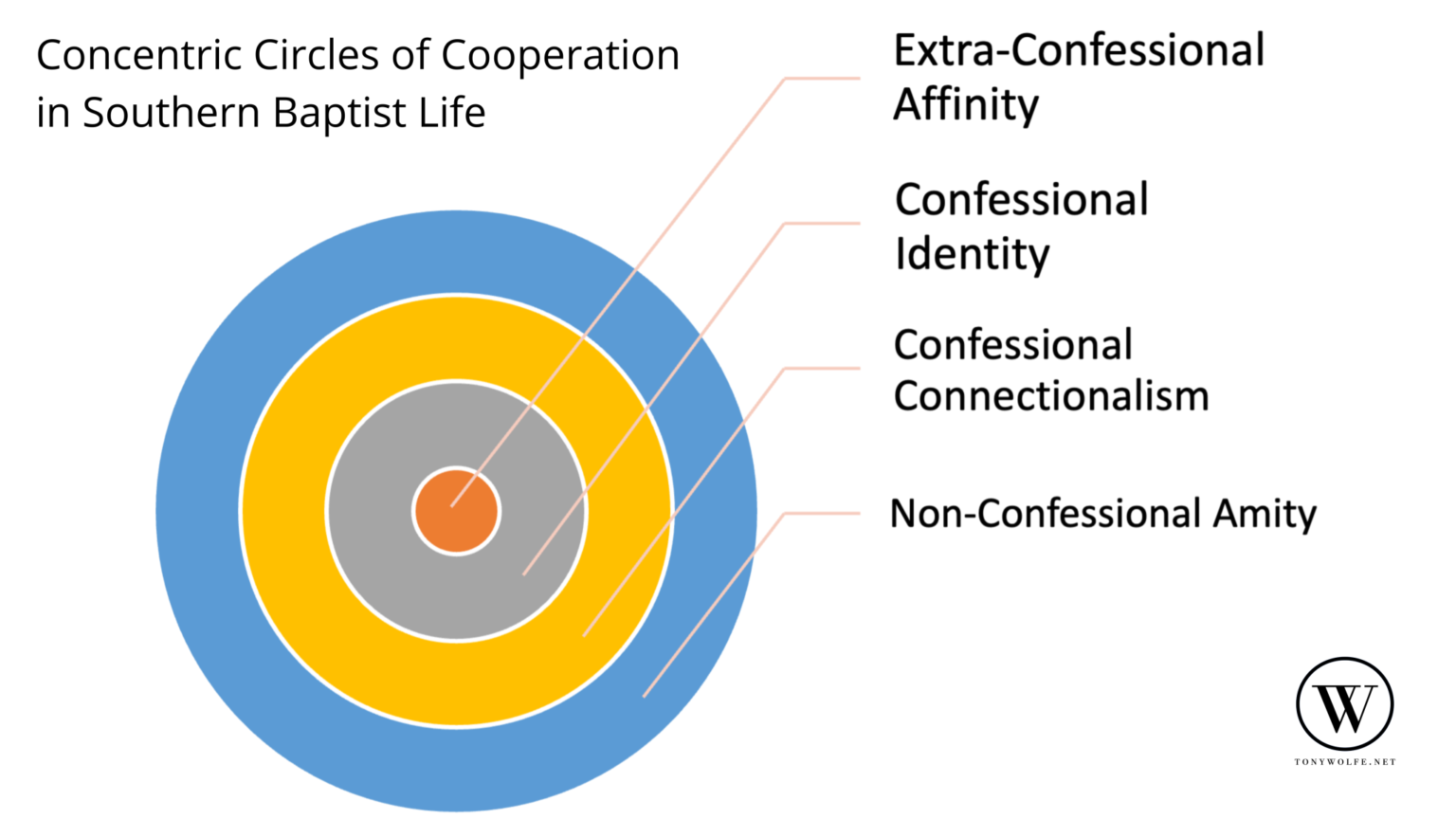

To this end, here are what I am calling “Concentric Circles of Cooperation in Southern Baptist Life.”

Non-Confessional Amity

(EXAMPLE: Larger Evangelicalism)

We start here because Southern Baptists have historically been, and are currently, part of a much larger Evangelical stream of Great Commission work. We can, and often do, join forces with other evangelical denominations or independent movements to advance shared biblical causes, as long as doing so does not require compromise on our core doctrinal tenets. Perhaps the idea is captured best in the last sentence of the BFM2000 Article XIV: “Cooperation is desirable between the various Christian denominations, when the end to be attained is itself justified, and when such cooperation involves no violation of conscience or compromise of loyalty to Christ and His Word as revealed in the New Testament.” Southern Baptists join forces with a variety of evangelical friends from time to time in an agreeable, amiable Christian spirit.

Confessional Connectionalism

(EXAMPLES: Southern Baptist Convention; Most State Southern Baptist Conventions and some Local Associations)

This is the first level, the most basic form, of a clear confessional inter-congregational missiology. Autonomous Southern Baptist churches choose to come together for Great Commission advance. The institutions and entities they create do not hold ecclesial authority over them. Rather, they exist to serve the Great Commission efforts of cooperating churches. In a way, the churches gather around the faith statement, but not necessarily through it. They hold a faith and practice which “closely identifies with” the Baptist Faith and Message. However, the resources they pool for their shared missional task can only be applied to individuals and entities which ascribe and adhere to (“sign off on,” as is commonly said) the Baptist Faith and Message. This affords SBC churches a functional confessional missiology without a strictly confessional identity. All of the churches do not necessarily hold to every word of the faith statement, but all of their cooperative work is guided and guarded by that faith statement. In this way, the SBC becomes merely a “voluntary and advisory” body, “designed to elicit, combine, and direct the energies of our people in the most effective manner” toward the advancement of the Great Commission (BFM2000 Article XIV).

Confessional Identity

(EXAMPLE: Southern Baptists of Texas Convention)

As the concentric circles of cooperation tighten, one finds more doctrinal alignment, and by extension, fewer member churches. Because Southern Baptist Churches are encouraged to organize “as occasion requires… such associations and conventions as may best secure cooperation for the great objects of the Kingdom of God,” (BFM Article XIV), they may do so even within the larger Southern Baptist mechanism. In fact, Baptist history would show that the purest forms of Baptist cooperation began locally, in associations, then grew into regional and state conventions, then eventually into a national confessional connectionalism. Associations and State Conventions have, for hundreds of years, defined their own parameters of cooperation. Many of them, such as today’s Southern Baptists of Texas Convention, have required churches to affirm a confession of faith in order to affiliate with and remain in good cooperation with the work of the association/convention (historic examples: 1655 Midland Baptist Confession of Particular Baptists; 1651 The Faith and Practice of Thirty Congregations Gathered According to the Primitive Pattern; 1656 The Sommerset Confession). The churches in these associations/conventions share more than a confessional connectionalism; they also share a confessional identity. The confessional statement is the door through which a church enters the network, and it continues to serve as their umbrella of cooperation. The Bible is still the ultimate rule of faith and practice for each church. The confession is not about defining orthodoxy. Rather, it is about defining parameters of cooperation. Each church agrees to be held accountable to the doctrines they commonly confess in the faith statement. By extension, each church agrees to show grace wherever biblical doctrines are not clearly defined in the faith statement. Again, it’s not about doctrinal regulation, but about parameters for cooperation through a shared “doctrinal accountability” (BFM2000 Preamble). Sharing confessional identity, the churches still choose to cooperate with the larger Southern Baptist Convention, in its confessional connectionalism, to accomplish their Great Commission goals. They also choose to work in good faith within larger evangelicalism, through non-confessional amity, when they deem such actions beneficial and appropriate.

Extra-Confessional Affinity

(EXAMPLES: Baptist 21 Network; Conservative Baptist Network; Pillar Network; Cowboy Church Network; Black Church Network; Korean Baptist Fellowship)

The tightest circles of Baptist cooperation are found in those pockets of affinity groups who not only confess the convention’s broader confession of faith, but also hold to a stricter set of doctrinal principles or identifying markers. These are sometimes called “tribes” in popular Southern Baptist language. I would submit that tribes, in themselves, are not a problem. Rather, it is tribalism that poses a concern for greater missional cooperation. It is good and healthy for churches who share affinity outside the parameters of the faith statement to gather for mutual encouragement and fellowship. They may even generate missional movement within their own affinity groups that further strengthens the core of the larger convention’s work. Like all other forms of associationalism, these are “voluntary and advisory bodies designed to elicit, combine, and direct the energies of our people in the most effective manner,” (BFM2000 Article XIV). Although more tightly aligned doctrinally and/or distinctively, they expand and enlarge their Great Commission impact when they work with the larger family of faith, through confessional identity, within confessional connectionalism, and outward into non-confessional amity.

Southern Baptist churches and organizations may fall anywhere on the spectrum of the concentric circles of cooperation. They may also cross between those circles either from time to time or as a matter of their consistent governance or practice. But the nature of cooperation in Southern Baptist life is, as of today, a multi-layered approach to good-faith cooperation for the fulfillment of the Great Commission in our neighborhoods and to the nations.

For the Southern Baptist Convention at large, the question moving forward is not necessarily the interpretation of one article of faith or another (although I do believe we need clarity on a couple of them, as was demonstrated this week from Article VI). Rather, it is whether we continue in the current pattern of confessional connectionalism or redefine the nature of our national cooperation toward confessional identity. I am confident that Southern Baptists can have this discussion with the mind of Christ, in good faith, and with sincere affection for one another. Hopefully, these Concentric Circles of Cooperation in Southern Baptist Life will provide a helpful framework for that discussion.